Ampersand Gazette #95

Welcome to the Ampersand Gazette, a metaphysical take on some of the news of the day. If you know others like us, who want to create a world that includes and works for everyone, please feel free to share this newsletter. The sign-up is here. And now, on with the latest …

&&&&

When Novels Mattered

I’m old enough to remember when novelists were big-time. I’m not saying novels are worse now (I wouldn’t know how to measure such a thing). I am saying that literature plays a much smaller role in our national life, and this has a dehumanizing effect on our culture. There used to be a sense that novelists and artists served as consciences of the nation, as sages and prophets, who could stand apart and tell us who we are.

Why has literature become less central to American life? The most obvious culprit is the internet. It has destroyed everybody’s attention spans. I find this somewhat persuasive but not mostly so. The decline in literary fiction began in the 1980s and 1990s, before the internet was dominant.

People still have attention span enough to read the classics. Americans still love literary books. People still have the attention span to read a few contemporary writers, and a sprinkling of reliably left-wing literary novels. It’s just that interest in contemporary writers overall has collapsed.

I would tell a different story about the decline of literary fiction, and it is a story about social pressure and conformity. What qualities mark nearly every great cultural moment? Confidence and audacity. I would say there has been a general loss in confidence and audacity across Western culture over the past 50 years. Everything feels commercialized, bureaucratized and less freewheeling today.

Furthermore, the literary world is a progressive world, and progressivism has a conformity problem. This accords with my experience. Conformity is fine in some professions. But it is not fine in the writing business. The whole point is to be an independent thinker, in the social theorist Irving Howe’s words, to stand “firm and alone.”

We have lived, for at least the past decade, in a time of immense public controversy. Our interior lives are being battered by the shock waves of public events. There has been a comprehensive loss of faith. I would love to read big novels capturing these psychological and spiritual storms.

Which brings me to the good news. Literature and drama have a unique ability to communicate what makes other people tick. Novels can capture the ineffable but all-powerful zeitgeist of an era with a richness that screens and visual media can’t match.

It strikes me as highly improbable that after nearly 600 years the power of printed words on a page is going to go away. I would put my money on literature’s comeback, and that will be a great blow to the forces of dehumanization all around us.

Excerpted from an Opinion Essay by David Brooks in The New York Times

“When Novels Mattered”

July 10, 2025

I took the names of all the famous novelists and literary critics out of this excerpt precisely because they’re not the point. The point is the novel, or, better said, fiction. And its uses.

About those now anonymous writers of words, be they originators of or criticizers of same: they’re not the point because they actually distract us from the point. Americans love to do that. Did you know? We say, fiction writing is foundering, and someone pipes in with, Yeah, but what about Ken Follett? By naming individual authors, we effectively obliterate the rest of the playing field.

Most commonly, we call these ‘exceptions.’ But are they? I would submit that they are not. Naming individuals or instances as exceptions can prevent us from seeing systemic patterns.

Look at the world of indie publishing right now. It’s thriving, going gangbusters. There’s BookTok, BookTube, Shepherd.com, and a squillion kajillion fan sites all about fiction.

Mr. Brooks, I am unrepentant when I tell you that novels still matter. Oh, maybe not the ones on the Bestseller Lists. But Amazon, Kobo, Apple Books, and Barnes & Noble do not sell books for fun. They sell them for profit.

True confessions: Unless you’re brandy-new to this newsletter, you know that I write novels. Yes, fiction. I write across several genres—mystery, queer romance, speculative fiction. All my books are metaphysical. I’m also mid-writing paranormal and cozy mystery genres.

Why do I write novels? Because I could never find any books about me or about the way I wanted to live in the world.

The same thing is true for Diana Gabaldon. She wanted to read a story about a long-term successful marriage, not a star-crossed romance. She couldn’t find any, so she she wrote Outlander.

Writing is meant to be reflective on several fronts. First, it reflects the inner world of its author. What she’s thinking, feeling, wondering about, wanting solutions for. Second, it reflects the outer world of its readers, and hopefully, takes them into their own inner worlds toward self-reflection as well.

A long, long time ago, I decided that I wanted my books to have a double purpose. [You be a Libra with five planets in Libra and a Gemini Moon—dual purpose might be my confirmation name.] I wanted them to educate and entertain, long before any cutesy media marketing wordsmith thought up ‘edutainment.’

This reflection is the true purpose of all artforms. It matters not whether they’re word-based. Dance, music, theatre, painting, sculpture, quilting … I could go on and on. All of it is for reflection.

And why do you suppose that is? So that we can see and learn from ourselves which we so often do by contrasting our lives with the ways others live theirs.

Some of us have taken to calling physical books ‘dead tree’ books, and so they are, but they are also living, breathing witness to the ways and means of living that, done well, and embarked upon openly, humanize us all.

Life’s all about choices, dear one. A lot of them related to time, and how you use yours. Give me a book, with a great character, and a complex storyline, or even better, a series of them every time over anything on a screen. I guarantee that I’ll learn something that makes my life better.

Oh, and if you want proof that I’m right about this, have a look at any one of my more than twenty fiction novels. Maybe I ought to send one to Mr. Brooks.

&

He Took My Story, So I Made a New One

Three times a day, my friend called.

My 60-year-old husband had told me out of the blue that he wanted a divorce so he could find someone with whom he could start a family of his own. In the weeks after my husband left, my immediate back story was that I was unlovable—an ancient tale rooted in childhood, and I was stunned by its force as it spewed from the depths.

After my husband left, people judged me. I understood. Loss is a constant and yet such a huge fear. We all want to believe that we can be immune from loss if we do everything right. I believed my husband and I had a wonderful relationship. Clearly, that wasn’t true.

All humans tell stories, and the most powerful story is the one we tell ourselves about ourselves. In so many ways, this story is our self. Who we were, where we came from and where we’re going.

This sudden ending destroyed our life together, but he also walked away with my story. He left me storyless. All I had believed about myself was smashed and lay on the ground in little pieces.

Day after day, my friend called, visited and invited me out. [I]n this way, she kept me sane by repeatedly telling me the story of myself. It was a story I couldn’t remember and could barely hear, full of bravery, strength and good humor in the face of adversity.

She held onto my story until I could again tell it myself.

Excerpted from a Modern Love column by Virginia De Luca in The New York Times

“He Took My Story, So I Made A New One”

July 18, 2025

Do you recognize the stories you tell that have become your signature stories? You know the ones I mean. You tell them whenever you meet someone new who has the potential to become a real friend. The stories are personal, even formative.

No, not precisely. The events were formative, and you memorialize them in your repertoire of stories about how I became who I am today. One of mine was that my dad was killed in a plane crash when I was five.

It’s a true story, on the level of the facts. I have the newspaper articles from 1963 to prove it, but what’s far more important, now some sixty-two years later, is what I did with those facts as I made them part of my life story.

For years and years I told the story the same way again and again. The subtext was: my daddy abandoned me. But he didn’t. Not really.

It took me a long, long time to come to this conclusion. You see, I was telling the story from his point of view—what he did. To me. On one level, it appeared to be true, but the real story, the truer story, the one that made me change how I told this story was that I felt rejected, not that he’d abandoned me. That told the same story from my point of view.

The moment I understood my own feelings which grew from the context of those facts, the story, as I told it, changed. I’d discovered the moral of the story, the one that helped me become who I am, so I didn’t need to tell it in the same way any more.

I can understand Ms. DeLuca feeling bereft, especially when it came to the story she told of her life and her marriage, and I so appreciate the valuable service her dear friend provided—to tell and retell and tell again the story of who she was till she could remember it for herself.

That’s why we tell stories again and again, Beloved. So we ourselves discern the moral, the learning, the thing that changes our story of ourselves. When rejection was no longer at the core of my self-story, it principally disappeared from my life.

Not all of us have the sort of friend that Ms. DeLuca did, but a friend isn’t the only story-delivery system in the world. A movie can do the same thing, a play, even a musical, a television episode, and of course, my old stand-by, a novel. Anything can … really. Because your whole world is a reflection of you.

Its function, whatever the story-delivery mechanism, is what the Victorians would have called an aide memoire, a memory-helper. Our own inner witness of our stories can do the same thing. As I advance in years, I am more and more convinced that stories are what help us remember who we really are.

And that very thing—remembering who we are—is really why we’re here. The true story of why you’re here is always available to you, dear one. You just have to let in the moral of the story, and then all the gloriousness of who you are will shine upon all of us, and what a blessing that will be.

&

Here’s a universal affirmation. It works every time, for everyone, always and forever …

We used this the whole time I was in the hospital, and we are still using it as we live through the repercussions of that time.

&

So, yeah, there was this plot twist, which, by its very definition was unexpected. You know what I did expect, though? To get home and immediately go back to life as usual, and it turns out, not so much.

I think the proper name for that is wishful thinking.

Except … the thing is, sure, the crisis is over. Thank you, Mother, but the healing is ongoing. When I got home I was still taking antibiotics. Now that’s over. I still have 3 of 5 doctor appointments to get done. Two of them aren’t even scheduled yet!

Antibiotics like to scramble my brain so writing is pretty much off the table. There are too many threads to hold onto as a discovery writer to risk writing, and then having to redo the whole damn thing once I return to full consciousness.

Not only that but the plot twist has caused, and rightfully so, some serious introspection, and has asked for some significant changes to everyday life—all of which take time, creating new habits, getting used to them, and remembering that things have changed.

I never in a zillion years would have thought that I’d miss my exercise bicycle the way I do, but, jeez, I do. A lot. I’m religious about it riding it five days a week, and now that I haven’t for a little over two weeks, and still have a week to go where it’s not an option, I realized just how much benefit it has given me.

As a result, not a lot of writing or publishing news, but I’m sure I’ll figure out a way to use this whole plot twist experience in a book. You know it. When it comes to plotlines, authors have no morals.

&

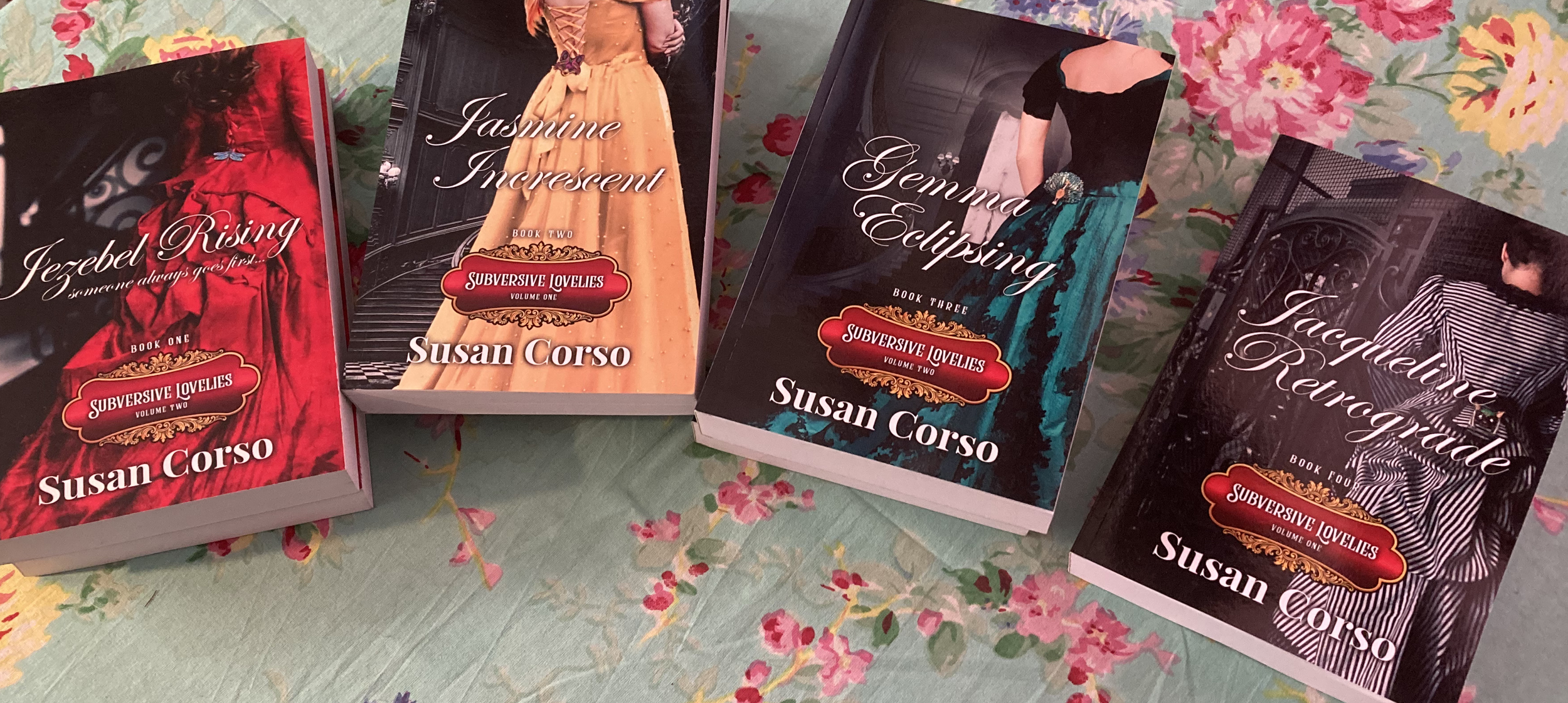

Soon enough, it will be time to feature the complete series of The Subversive Lovelies. Here are the first three-and-a-half books.

As always, whichever book of mine you enjoy, would you please leave a stellar review, if you loved it? Those reviews are how others find indie authors like me. I really appreciate it!

Reviews really are the engine that powers the career of an indie author.

&

Tony Amato is my favorite editor for lots of reasons, but mostly because he has an uncanny ability to seek, find, recognize, and polish the truth of a writer’s voice. There’s a good reason he calls what he does book-husbanding.

The coolest thing is, the genre doesn’t matter. His skills apply. I write mysteries, romances, speculative fiction, essays, and nonfiction. Others of his roster write for academic journals, radio plays, micro-fiction, erotica, memoir, poetry, screenplays, essays, workbooks, teleplays—you name it. His talents help with any kind of writing.

If the truth of your voice as a writer is in need, may I encourage you to reach out for Tony’s spectacular book-husbanding? Seriously, this is the guy. He’s edited my books for more than 20 years, so I ought to know. Find him here. Oh, and here’s his substack Subscribe here.

&

As you can imagine, being mid-plot twist,

I did very little reading,

so no book review in this issue.

&

Are you waiting for a sign?

How about this one?

Books have always been

full of magic for me.

Are they for you?I hope so.

I think books are a way to try on

different lives than the ones we’re living.

Sometimes those try-outs

actually set us free of

unreasonable expectations,

lifetime disappointments,

and all manner of trauma.

Other times those try-outs

help us set others free of

the same.

A good book is a world unto itself.

Give yourself a gift

this week, Belovèd,

and read a good book.

I am, without doubt, certain that And is the secret to all we desire.

Let’s commit to practicing And ever more diligently, shall we?

Until next time,

Be Ampersand